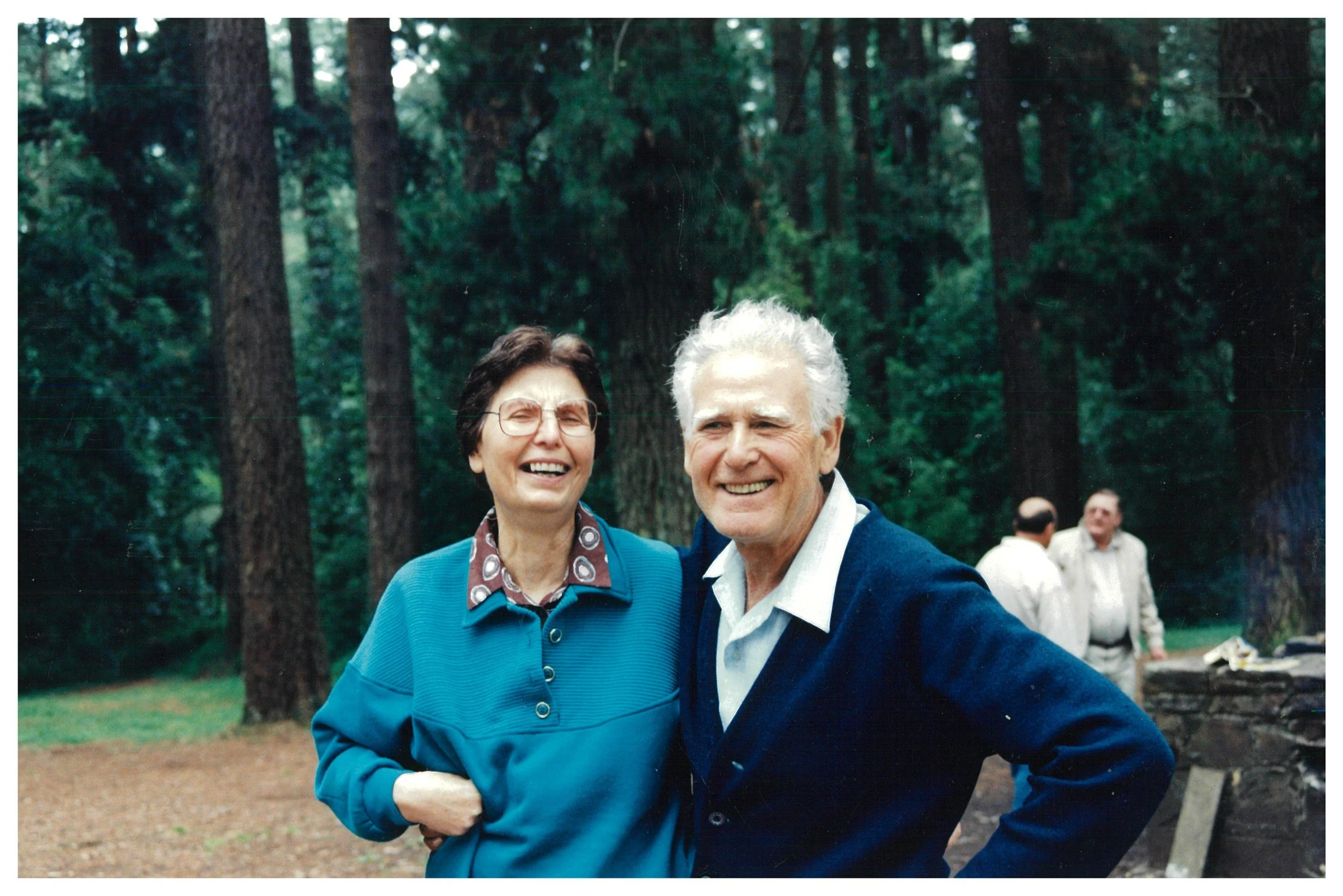

Gaetana Antonuccio and Franco Podimane

“If you ask me what I have learnt from having lived so long, it is how we are all capable of change.”

This piece was written and contributed by Nancy Podimane, Gaetana Antonuccio’s daughter, from Gaetana’s perspective.

I was born into poverty and upheaval.

It was 1934; the year Italy won the World Cup. And the year when Mussolini won a general election with 99.84% of the vote. More a referendum than a true election, with only one party running for office. Still, it was the last election of any sort held under Fascist rule.

I remember my mother vividly to this day. She was the daughter of a Maltese family that had emigrated to Gela, a Sicilian fishing village of 30,000 people. She had married at a young age and birthed five children before my father was sent off on Mussolini's war of conquest which we were told would restore Italy to the greatness of the ancient Roman Empire. Alone, she provided for a family of six. Italy had had a humiliating defeat to the Ethiopian army in 1896, and Mussolini's plan was to avenge this blow to the national pride and become a major player in the colonial scramble for Africa. Moreover, the Great Depression of the 30s had undermined many economies including Italy's, so Mussolini sought raw materials and new markets. Hitler looked on with glee as the League of Nations failed to stop the Italian dictator's invasion in 1935; an event that is seen by many historians to have emboldened Hitler. About 6000 Italian soldiers lost their lives during the second Italo-Ethiopian war which ended in 1937 with 1,500 returning home wounded, one of these being my father. Small fry compared to the 300,000 Ethiopians who lost their lives as a result of the invasion.

He was a silent presence in the house when he returned. That period of my life is an empty chapter, and when he died of complications following his injuries, my mother was never to speak of him again. We asked no questions, as if we had all signed a secret pact.

Today, I am almost enraged by the fact that I know so little about my own father and have started grieving him late in life as I read more about the history of the times, whose propaganda had evidently silenced our thoughts.

‘Gaetana Antonuccio’, photograph by unknown.

‘My mother, Concetta Iannizzotto’, photograph by unknown.

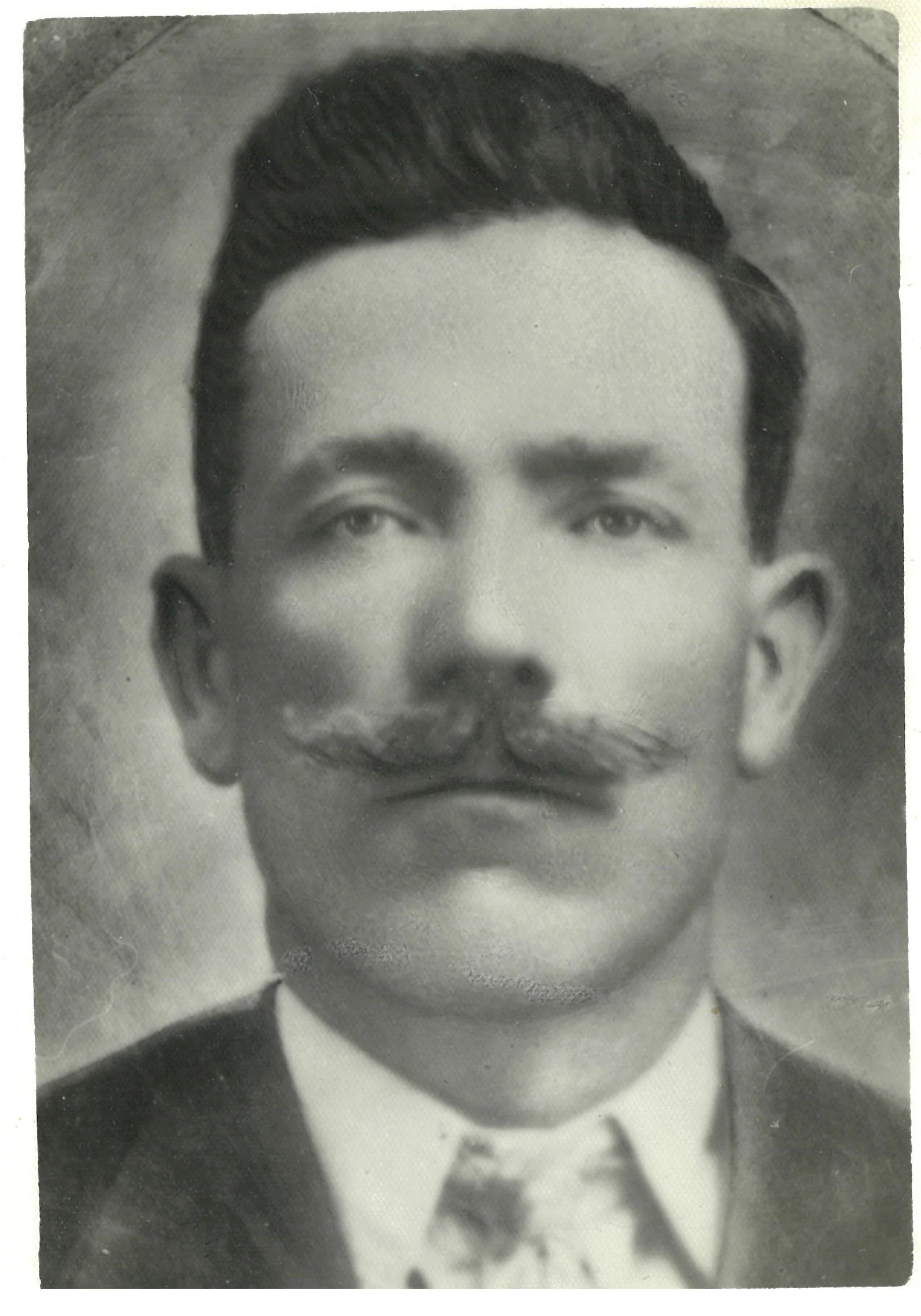

‘My father, Nicola Antonuccio’, photograph by unknown.

‘Italy wins the world cup’, photograph by unknown.

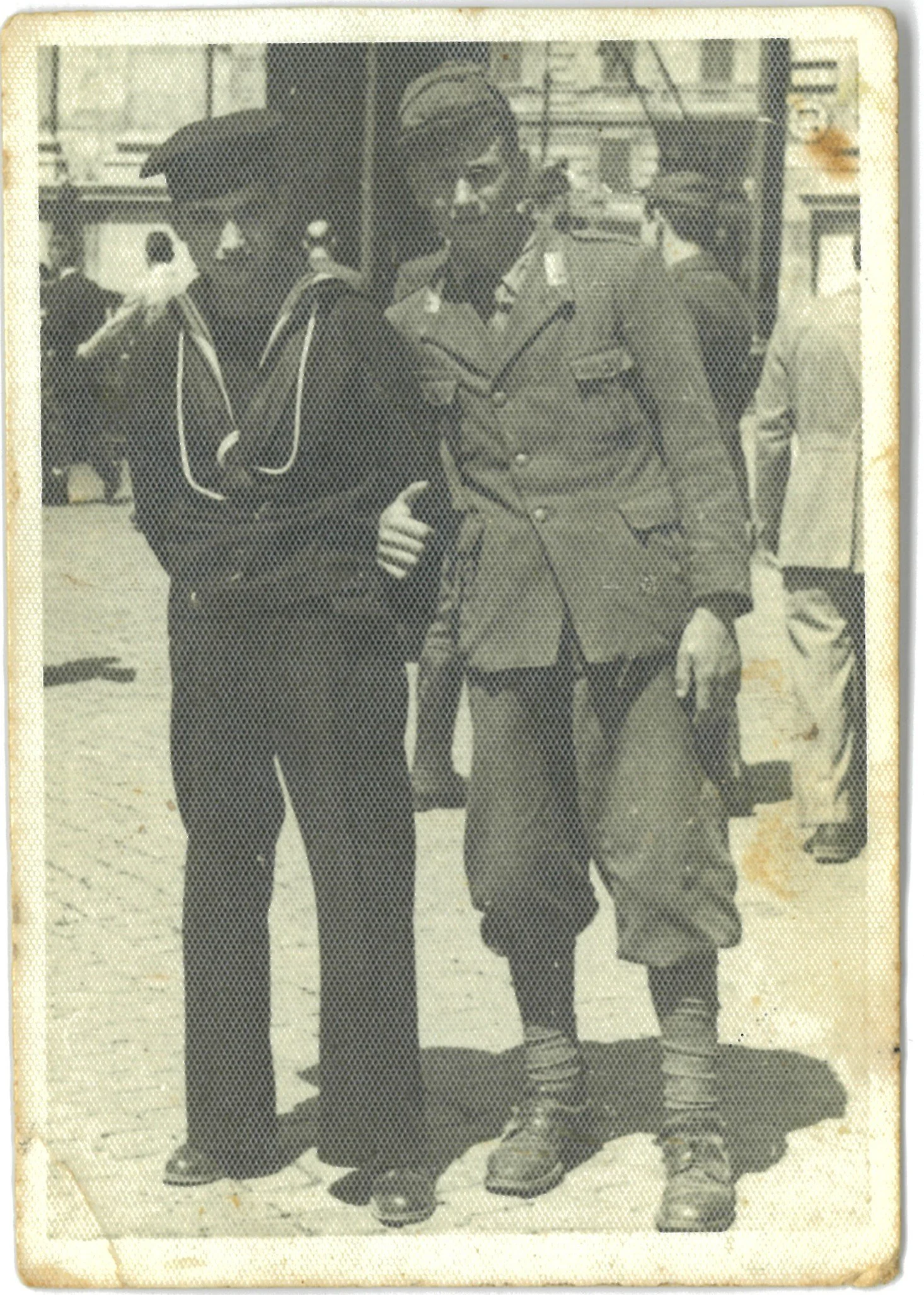

‘Franco and friend in hiding’, photograph by unknown.

‘In the countryside, wearing a white dress with my big sister Maria’, photograph by unknown.

‘My brother Angelo in uniform’, photograph by unknown.

My mother supported the family by sewing, doing the odd jobs and pawning the family jewellery. She was a war widow but there was no welfare state at the time. Families who could not put food on the table sought help from the wider community. My sister, Maria, ended up living with a relative in the next town and suffered an acute sense of abandonment. I was aghast at this arrangement and decided single- handedly to rescue her. One day, I caught a bus and after making enquiries managed to locate my aunt's house. I packed her bag and quickly led her to the bus stop where we held hands in silence. I believe this episode had a detrimental effect on my sister and forever undermined her trust in us.

The second world war brought even more hardship. The women were being invited to donate their gold to The Duce, for the war effort, and my mother gave him all the gold we had.

My brother, Angelo, smitten by Mussolini's virility, joined the army in Rome, but deserted soon after. He walked from Rome to Gela on foot for 3 weeks and one morning we saw him arrive in his underpants. More than one young man took refuge in the countryside trying to avoid conscription, including my eldest brother Peppe and my future husband Franco. We children knew their hiding places.

Whilst Mussolini was a cult figure, the Fascist ideology did not have universal consensus. Nor were the German soldiers held in great esteem. I remember asking what a Jew was after hearing about a local Jewish noblewoman being offered a hiding place by the local nuns. My most vivid memory, though, is of the day we fled our home on horse and cart and took refuge under a bridge in the countryside, as bombs fell over our heads. We slept under the canopy of an ancient carob tree which still stands to this day. I will never forget catching sight of the face of an American pilot as his My brother Angelo in uniform In the countryside, wearing a white dress with my big sister Maria Spitfire swooped over out heads. The Battle of Gela in 1943 between the Allied and Axis forces was the opening act in finally bringing down the regime.

When I hear fireworks today, I am always taken back to that frightened little girl and her Spitfire hero.

I had a carefree existence after the war, until I was offered the opportunity to go to school, which any child of good sense would refuse. No one in my family had gone, so it was not clear to me why I should be the first. What finally convinced me were my brother's bribes. Angelo had found a job in a pasta factory and I was offered a lira a week to attend school. He was the most enlightened member of the family as he had crossed the strait of Messina.

I liked school and, in order to continue my studies, moved to Vittoria to live with my sister, Vicenzina, where I could attend il Magistero.

I became a teacher and soon after started to work. It was a happy period of my life and I remember with great pleasure the travelling literacy program where I visited many homes teaching children to read and write.

By this stage, my three older siblings had all left home and got married. Vicenzina, who had hosted me in Vittoria during my studies, emigrated to Australia, and together with her husband, opened a milk bar in New Farm, Brisbane.

I adored my mother. She had always been a loving, honest, trustworthy woman who seemed defenceless in the face of unscrupulous individuals, so my greatest desire was to stay by her side and protect her. They would call us a comet with its tail, so close was our bond. And even though I was being courted assiduously by more than one young man, I had no interest in straying far from her.

Then the unthinkable happened. She had a stroke and died in a matter of hours.

My life no longer made any sense without her and I entered a period of confusion and depression.

Had it not been for her sudden disappearance, I would not have done the unthinkable: accept a marriage proposal from a friend of my brother's who had emigrated to Australia in 1956.

This way I would be near my eldest sister who I dearly missed and I would get away from Gela: a place which now held too many unhappy memories.

‘Attending school’, photograph by unknown.

‘Teaching students in their homes as part of a Literacy Program’, photograph by unknown.

‘Attending the Magistero College’, photograph by unknown.

‘Teaching in a public school’, photograph by unknown.

The man I chose to marry was born in Gela in 1924. Although extremely handsome, he was known to have a hot temper. My brother was not really in favour of this marriage as he thought me worthy of someone more refined and educated. I think my decision to migrate was primarily dictated by the hopelessness I felt after losing my mother. Otherwise, I would not have left.

Franco had learnt the trade of cooperage; a skill with no demand in Australia in 1956. Perhaps, if he had gone to Buenos Aires, our family history would have taken quite a different turn. His good friend, Giuseppe, had offered to sponsor his passage to Argentina but Franco opted for Australia, where a few acquaintances had settled. He had no real need to migrate as he had a job, but all the opportunities that the post war offered had an intoxicating influence on many. If you were at all ambitious you would be jumping on the next boat; which is precisely what he did.

He quickly found a job, and soon after bought a house in Melbourne.

Then he thought that marriage would complete his life. He frequented some local women but could not establish a deeper link, possibly due to the language barrier. When my brother told Franco about our mother's sudden death and how distraught that had left me, he reached out. One letter led to another and eventually I could imagine myself there sharing all the challenges that he described in his letters.

Our marriage was celebrated in Brisbane but I was not to stay with my beloved sister and her family for long. Franco had established his life in Melbourne and once I had experienced the humidity of Brisbane's tropical climate I was more than happy to leave. In the long run, Melbourne revealed itself to be a good place for an Italian as it boasted the biggest Italian population of Australia and saw a more rapid expansion of Italian traditions.

‘Wedding photo’, photograph by unknown.

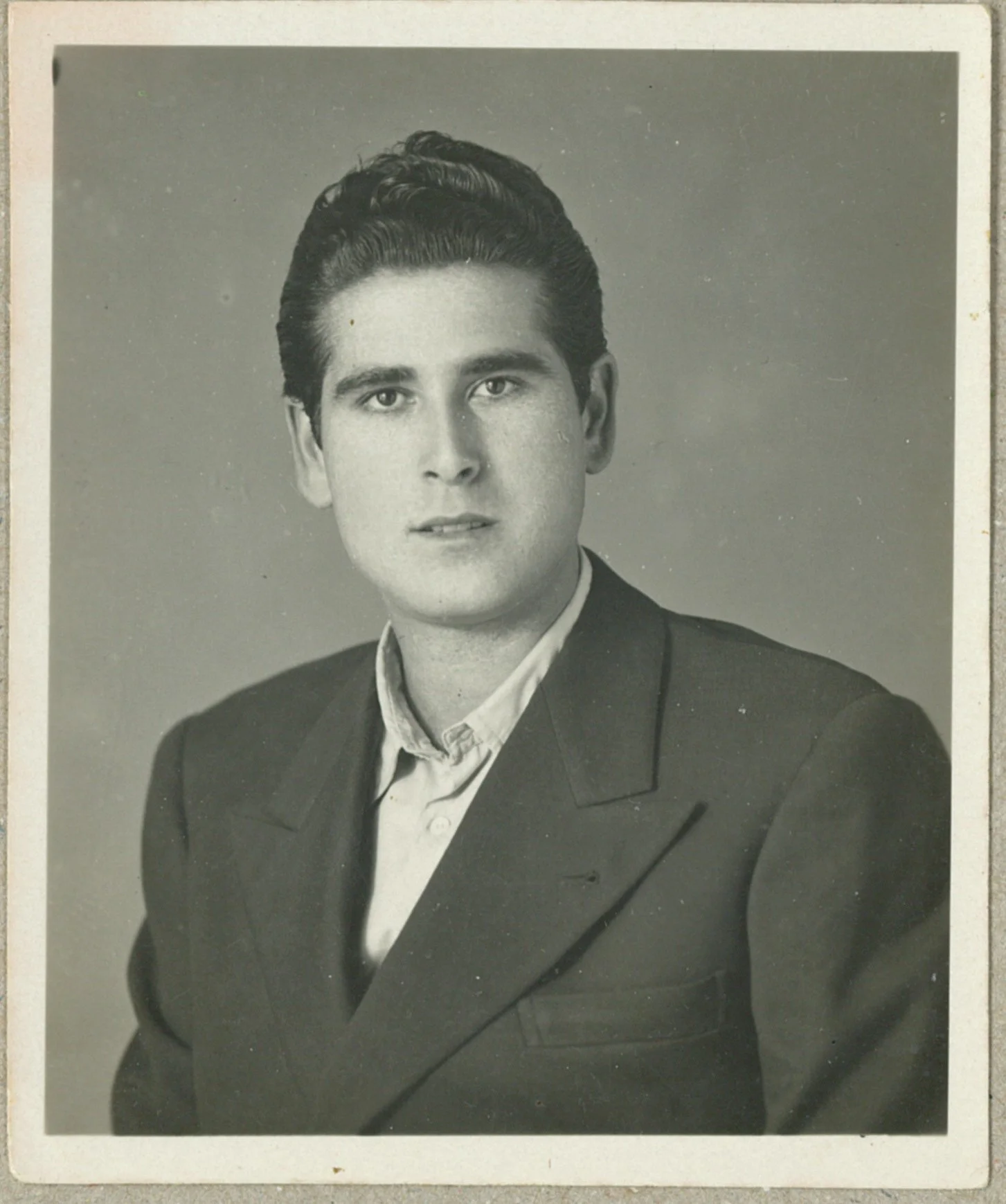

‘Franco Podimane’, photograph by unknown.

Still, I did not feel this was really my home. We worked, saved our money, frequented other Italians who were on the same trajectory, but never felt a sense of warm belonging.

It was natural that we would be subject to some prejudices. For the older generation of Australians who had served in WW2, we were the Fascists, friends of the Nazis. For others, we were dagos; dark, garlic smelling rowdy individuals with strong family ties, prone to temperamental outbursts. Perhaps what aggravated this antipathy was also our tendency to stay sober, work hard, save money and buy homes. While some of Franco's colleagues would run to the pub, drink and bet their salaries away on horse and dog races, Franco would either go home and hand his salary over to his wife or clock on to do an evening shift, earning the disdain (and probably the envy) of his fellow workers; becoming a working-class victim of the tall poppy syndrome which Australian culture is sometimes renowned for.

No wonder he would come home from work feeling edgy and frustrated. And no wonder a peaceful family life was difficult to achieve. It was a mix of things which got me thinking that we were probably better off going back to Sicily.

My niece from Sicily had come to Melbourne with her husband but soon missed the conviviality of her hometown, Vittoria, and left. Filippo, Franco's brother, threw in the towel after a few months, declaring; 'Life here is all about work!' Perhaps they were right, I began to think.

In the meantime, my sister in Brisbane was also plagued with doubt. 'Our shop is doing well, but my son is an unruly, angry boy who no longer wants to go to school. In Vittoria we were surrounded by so much affection.' They eventually left, which made me feel even lonelier.

In the meantime, Italy was going through an economic miracle and stories coming from our Sicily led my husband one day to aptly observe that 'Italy had become the new America': government investments, new industries, a generous welfare system, universal health care, worker's rights and pensions.

We had for years been sending money to our relatives back home, but we were soon to discover that they were not as badly off as we had imagined. America had given Italy $12 billion through the Marshall program for the post war construction and to keep the communist spook at bay. And by the 70s, Italy had become the fifth most industrialised country of the world.

‘Franco with a kangaroo’, photograph by unknown.

‘Vicenzina and family in Brisbane’, photograph by unknown.

‘Waving goodbye, on my flight to Melbourne’, photograph by unknown.

I managed to convince my husband that we had achieved enough material security in Australia and that we should be more adventurous with our lives. Why not go on a road trip around Italy? After all, we knew so little about our own country. Franco liked the idea. We had travelled around Australia and seen lots of trees and desolation. Camping, snakes, barbecues was not the language we spoke. And the steely grey sea was always freezing. Evidently, we did not have the imagination to embrace this landscape and make it our own. We would always be misfits here.

So in 1967 we packed our bags and left. The plan was to travel around the country and then stay on if we liked it. My daughter, Nancy, now aged seven, was beside herself with excitement. My sister, Maria, decided to tag along. So off we went on the Galileo Galilei. She had been built in 1963 for the Italian emigrant trade, and along with her sister ship, the Guglielmo Marconi, can boast to have transported hundreds of thousands of Italians across the oceans.

Unfortunately, I suffered from sea sickness as I was to discover, so I cannot say I enjoyed the crossing, though every comfort and form of entertainment was provided for. We had not experienced such luxury and felt it was a gateway to a new life. One event certainly made it memorable; the six-day Arab-Israeli war broke out just as we were in line to cross the Suez Canal, bringing about its instant closure. We were forced to take an alternative route all around the coast of Africa prolonging our journey by weeks.

Landing in Messina was truly a joyous affair with relatives at the port to welcome us back. A whirlwind of friends and family soon filled our lives, just as we had hoped.

We bought a Fiat 600 to do our grand tour of Italy and set off; four people and their luggage. And got to know our country far and wide, as we drove leisurely for months, taking in all the beauty we had heard about but never seen. Fortunately, we knew a few people scattered around the peninsula, because the post war period saw a mass migration of southerners to the industrial centres of Turin and Milan. But we also had people to visit in Florence, Taranto and Rome.

Australia had become a far away memory and we even forgot our English. Our daughter could not believe how many people we knew and how friendly everyone was. How there was this instant warmth that would envelop you and make you part of things. As if a veil of invisibility had fallen off and people could finally see us. Once back in our home town someone suggested we buy a shoe shop that was for sale, in partnership with my aunt who was travelling with us.

We were not business people and had never run a shop, and perhaps this was the reason why things got rather complicated, quite quickly. Decisions were being made that did not suit everyone and soon the trust began to wane. Still, the shop stocked wonderful shoes and became a focal point in the town. We took pride in selling the latest models, at competitive prices.

But given that relations were souring we realised the situations had become too difficult to manage. Moreover, the discovery that an older member of the family had developed a morbid attachment to my daughter made it mandatory for us to move away. Our adventure was well and truly over after two years. Still, coming back to Australia was a shock. My daughter withdrew into herself and refused to speak to anyone at school. Franco reluctantly went back to being a factory worker and I applied for a new teaching position. Eventually, we settled into a predictable routine, grateful, at least, to have left all our problems behind us.

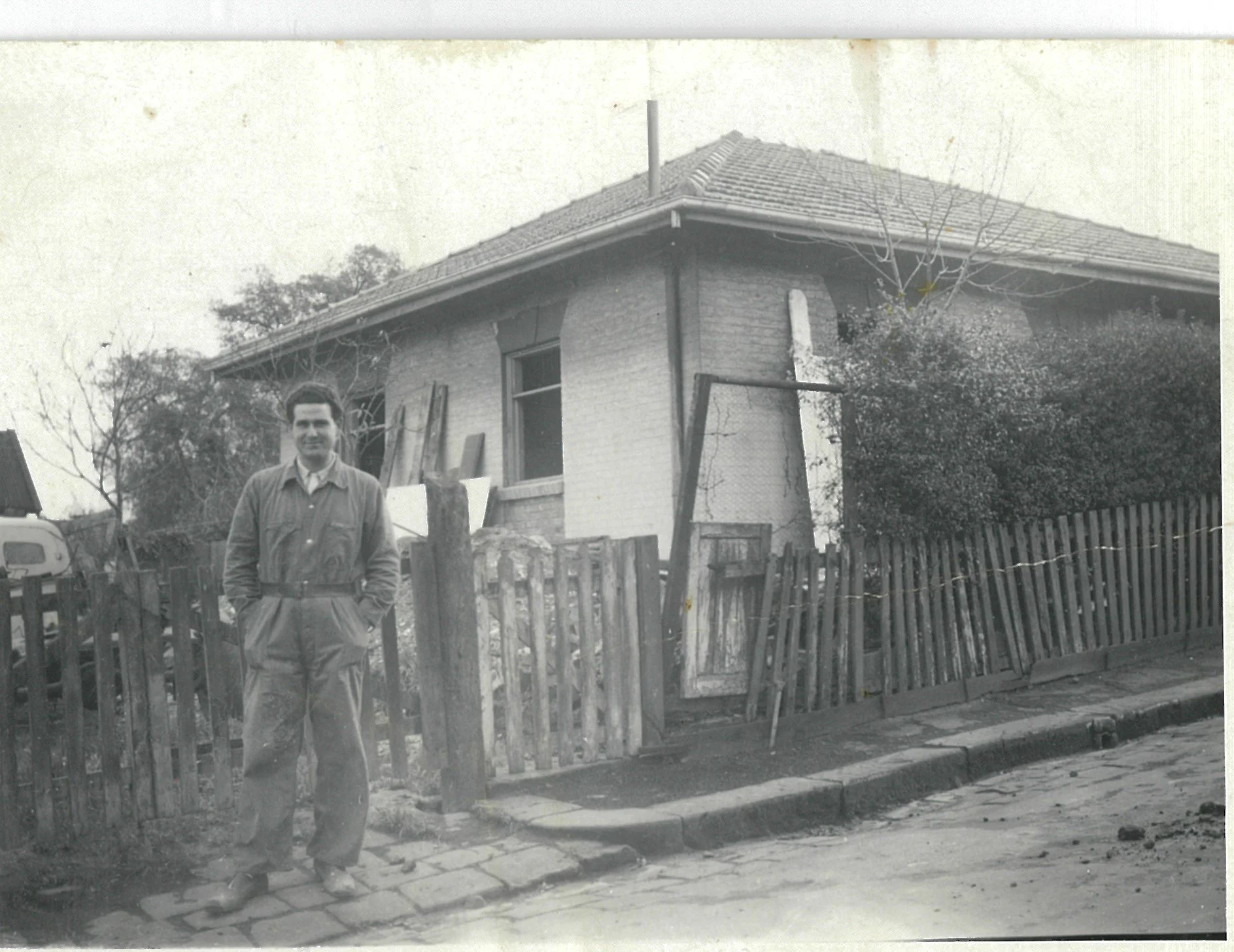

‘Franco and our first home in Richmond’, photograph by unknown.

My arrival in Richmond was welcomed by all the elderly residents who lived there at the time. I was given a bunch of flowers and a card. There were two widows, two bachelors and a married couple with children; Mrs King, Mrs Edwards, Mr and Mrs Taylor, Les and Johnny, They would always smile and bring presents to mark important occasions like Christmas, or the birth of our first daughter. Maybe it was just a packet of biscuits in a brown paper bag, or a book about Australian trees.

I was keen to try everything, but nothing tasted familiar. The biscuits were far too buttery, canned food was laden with sugar, and the ice cream too creamy. Gravies, dripping and greasy food abounded, and my first encounter with a meat pie was also my last. I almost fainted when I saw a neighbour drain off the fat from his roast to reuse the next day.

Australia of the 50s was quite a rudimentary country in terms of food and fashion; and a young Italian woman like myself could find nothing to titillate her taste buds.

Richmond was a working class suburb full of eclectic houses, narrow streets and factories. Franco had bought an old rambling Victorian home with a large garden and cellar.

As we had more rooms than we needed, we offered accomodation to those who had just arrived in Melbourne whilst they looked for a job and house. Many Greeks and Italians were moving into the area.

Eventually, my last sister, Maria, emigrated from Sicily and came to live with us. She had no education, nor husband, so felt alone and vulnerable but she found a job in Pelaco and became a machinist.

I studied English and learnt to speak it quite fluently. In fact, I was able to help many acquaintances and became something of a focal point in my community; they would come to have a letter read or an important document understood.

On a more personal level, married life proved difficult. I had been the youngest in my family and a little spoilt. I was sensitive, dreamy and unfamiliar with the gritty realities of life. I was also a young feminist of sorts and did not have a compliant bone in my body. Moreover, I had no understanding of men, nor was I patient enough to describe my feelings and aspirations.

Having my sister live with us further complicated things.

I started to work as an Italian teacher and was involved in setting up some language programs funded by the Italian government, through CO AS IT, to promote the learning of the language and culture. Saturday morning classes were set up in various locations across Melbourne for the children of immigrants, to ensure they learnt the language of their parents. I was responsible for the Clifton Hill centre which ran three classes.

I also taught evening classes to adult students and in secondary schools.

Franco worked in many factories throughout the city and eventually landed a job in the State Electricity Commission as a fork lift operator. This job offered good working conditions so he stayed on until retirement. However, quite a few of Franco's colleagues, like Franco himself, contracted cancer later in life, possibly due to the many substances containing carcinogens present in the workplace. Our awareness of such things was fairly limited at the time.

We had many opportunities to socialise with other Italians and saw the birth of many regional clubs that would organise dinner dances at the weekend, and mark every festivity with a social event- picnics, lunches etc. Sicilians set up a host of clubs based on town allegiance; Vizzini, Ibleo, Solarino, Sortino, Ramacca. And though Melbourne was a multicultural city, the different ethnic groups seemed to stick to their own kind and our closest friends were all Italian, mostly Southerners, like us.

I had always been a cinema buff and loved going to the movies, leaving my husband at home to babysit our daughter. And when Italian films finally made an appearance, the whole family could go together.

An Italian gelateria had just opened in North Melbourne and the family would often set off, on foot, on a summer's evening, to buy a gelato. On the way we would invite other Italian friends, who were lingering in their front gardens looking for a respite from the heat, to join us. The three- kilometre walk was full of nostalgic storytelling.

‘Maria’, photograph by unknown.

‘Deck games on the Gallileo Galilei’, photograph by unknown.

‘Saturday Morning Italian Class’, photograph by unknown.

Photograph by unknown.

‘Clubbing with friends’, photograph by unknown.

‘Family and friends’, photograph by unknown.

A number of events stand out after our return from Italy in 1969.

The birth of a much desired second child, also a daughter, in 1971.

And the conviction that we would be happier doing what all the other Italians were doing: moving out of working class Richmond to a more middle-class suburb. Every weekend we would peruse a range of houses; one was too big, the next too small, either too close to the main road, or too far from the schools. On and on went our interminable search.

We finally decided to buy a block of land in Bulleen and got an architect to draw us the dream home. We spent months pouring over the plan, making adjustments here and there, and then, one day, out of the blue, we bought a house in a suburb which was a little further out, Lower Templestowe.

Few Italians had settled into the area and we were surrounded by young Australian families who essentially ignored us. Even less enticing was the fact that you were obliged to get into a car to buy a bottle of milk. No one lingered in the streets for a chat. In fact, there was absolutely no one in the streets, except on Sunday, when men with lawnmowers would take to their front lawns. Only the sterile shopping centre offered signs of life. The spontaneous, down to earth life of Richmond with its architectural pirouettes, where you bumped into people, walked everywhere, caught any number of trams and trains to the beach, to the city to anywhere worth visiting, suddenly revealed itself for what it was: a more dynamic lifestyle and the closest I would ever get to feeling at home. But I kept my mouth shut, as it had been me who had pushed all these months for this radical change, dragging my whole family behind me.

One day, my youngest daughter, Gabriella, came home from the local primary school and shut herself in the bathroom, until dinner time. She had used Franco's razor to shave off her eyebrows. My blood was boiling as she calmly explained how different she was to the local blonde, blue-eyed kids, with her dark Mediterranean complexion. Suddenly nothing made sense anymore. We were living the dream, but it felt like a nightmare. Fortunately, we had not sold our house in Richmond and though Franco had grown fond of all the extra space, he understood that something was amiss and we moved back.

And Richmond became our final destination. We have never moved anywhere else, though over the years it has changed. We still love its earthy, comfortable feel, and the many realities represented here, though now it is more affluent and all the factories have been converted to apartments.

I remember the 70s and 80s as a particularly turbulent time of rebellion and change both worldwide, and in my own household.

We Italians tended not to embrace the values upheld in Australian society which afforded our young people a lot of freedom. Many immigrants lived in a time warp, sticking to traditional family values, as if frozen in time. Their broken English and limited Italian made them oblivious to the social changes happening both in Australia and in their native Italy, where conservative institutions and ideals were being challenged and young people and women demanded new rights.

I cannot say I was well equipped to deal with the increasing requests of my daughters for greater freedom. My husband thought we were giving them too much; my daughters thought they were not getting enough. I tried to bridge the rift between father and daughters, earning criticism from both.

The generation gap most families experienced was exacerbated in our case by the cultural gap. Our children fought two battles at once and only much later did I realise the impact this was having on their mental health. Moreover, their desire for independence as single women exposed us to the criticism of some members of the Italian community who looked upon such aspirations with great suspicion.

I eventually lost both daughters to the greater world. I guess my generation came looking for the bread, but they wanted the poetry, which they found elsewhere.

As a result, Franco and I have travelled to Europe quite often to visit them.

Nancy left Australia in 1993 and settled in Rome: a gutsy city with an infectious, zest for life. Gabriella eventually settled in London in 2005, seduced by its array of endless opportunities.

It is always difficult to come back to the clean, green, quiet of Melbourne after experiencing the chaotic intensity of life abroad.

All in all, we have probably visited Europe about twenty times in our attempt to keep all our family ties alive, including trips to Sicily to visit my older siblings.

When Franco retired he set up an Italian pensioner's club in Richmond, and enjoyed the role of president for a number of years, organising excursions, lunches and moments of collective sharing. Unfortunately, the number of Italian pensioners still alive has dwindled, and there is only one group left, operating in Collingwood.

Now that I am much older and cannot travel, I am happy that my eldest has moved back permanently to offer me support. Still, I miss Franco enormously.

His death in 2015 to cancer truly shocked me. Suddenly, I was alone and missed his garrulous, vital presence. We would regularly walk around the city and observe its transformation, crossing parks or strolling along the river, exploring new suburbs we knew little about. I pine for our carefree ramblings.

We both liked reading to keep apace with the news from abroad. I have always followed the advancements of medicine closely and like helping friends and family, by letting them know about new treatments and cures.

I worry about my own health, always searching for a better outcome, driven by a desire to stay independent. To this end I do exercises, eat healthily and go on walks. My greatest nightmare is having to go into a nursing home; but my daughters have promised me they will never do this and I am confident they will keep their word.

Christmas is now a special moment for me as I look forward to seeing my daughter Gabriella and grandson, Bruno, from London. We go on picnics, visit the thermal waters in Mornington or the Hawthorn pool and try out new Asian restaurants; fleeting moments I have grown to love, which given my advanced age, I cannot take for granted.

Bruno was born in 2010 and his arrival was a rebirth for us all. Franco and I were over the moon with joy: a grandchild and a boy; something we had never experienced before. It softened our hearts and filled us with such love and optimism.

Now that he is a teenager he likes skateboarding and exploring all the platforms on his phone. I question whether I have anything to offer that can be of interest to him. He belongs to the future where I feel I have no place. Nevertheless, I am genuinely moved by his warm affection for me, and I look forward more than anything else to his visits.

I have learnt to operate a mobile phone, an Ipad and a computer, which facilitates communication and my desire to be kept informed. And despite the fact that many of my peers have passed away now, I make a point of keeping in contact with their children, many of whom feel a strong connection with Italy, in spite of having grown up here.

I lead a comfortable life but have never really strayed from my modest beginnings. I treat money with respect because it came with sacrifice and sweat. I can honestly say that I have never fully shaken off the complex of being a second class citizen here. There is no longer the overt racism that characterised earlier periods, but I notice a condescending or patronising attitude, at times. This problem is now exacerbated by being elderly, which in itself attracts much prejudice.

Of course, I am proud to have reached the age of 90 but I cannot say that it is pleasant to see the body slowly betray my desire to live a full life. Unfortunately, there are constant trips to the doctor and I am conscious of becoming a burden on others. I have learnt to find joy from simple things: a trip to the park to bask in the sunshine can become a blissful moment.

Of course, I am proud to have reached the age of 90 but I cannot say that it is pleasant to see the body slowly betray my desire to live a full life. Unfortunately, there are constant trips to the doctor and I am conscious of becoming a burden on others. I have learnt to find joy from simple things: a trip to the park to bask in the sunshine can become a blissful moment.

‘All packed up, ready to go’, photograph by unknown.

‘Dinner on the Galileo Galilei’, photograph by unknown.

‘Rome, 1967’, photograph by unknown.

‘Touring on a Fiat 600’, photograph by unknown.

‘Our second daughter, Gabriella’, photograph by unknown.

‘On a 20-day European Tour, back row on the left’, photograph by unknown.

‘Richmond Italian Pensioner’s Club’, photograph by unknown.

‘On our daily walks around Richmond’, photograph by unknown.

‘My brother Peppe and sister, Vicenzina in Sicily’, photograph by unknown.

‘Picnic at Edinburgh Gardens, Xmas 2025’, photograph by unknown.

‘Bruno and Franco’, photograph by unknown.

Photograph by unknown.

‘Visiting my daughter Gabriella’, photograph by unknown.

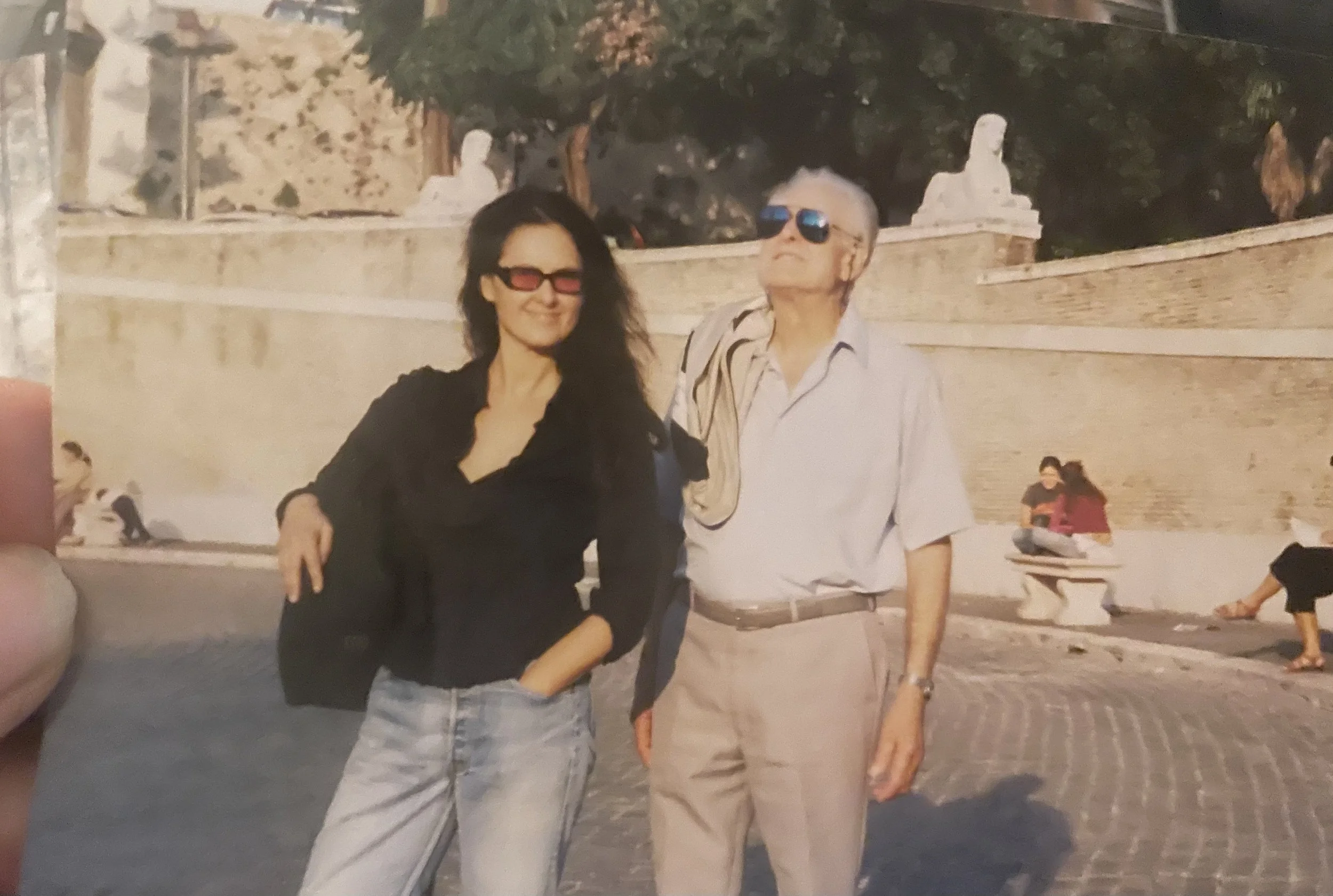

‘Franco visiting Nancy’, photograph by unknown.

‘With my grandson Bruno’, photograph by unknown.

‘Botanical Gardens with Tom’, photograph by unknown.

Photograph by unknown.

If you ask me what I have learnt from having lived so long, is how we are all capable of change. And the greatest sense of satisfaction is the ability to evolve and not remain imprisoned in our habits. Even as an older woman, I am still learning to say Yes rather than No; and to feel that sense of liberation in doing so.

Of the 300,000 people who emigrated to Australia from Italy over a twenty year period, only 20,000 ever went back; and around 78% became Australian citizens. Franco and I belong to the minority who never applied for Australian citizenship, even though Australia became our permanent residence.

Our gratitude towards this country for the opportunities and tranquillity it has afforded us is unequivocal, but we have never aspired to 'become' Australian, as it necessarily involved giving up our Italian citizenship. An impossible prospect for us to accept, psychologically: for our inner world thinks, speaks and dreams in Italian; and our language is the maternal embrace to which we belong.

Gaetana passed away, suddenly, of a stroke on 5/01/2025 in the presence of Bruno, Gabriella, Nancy, and her partner, Tom, after a joyful Christmas spent together. She was at home.

‘Gaetana Antonuccio: 24/2/1934 - 5/1/2025, Franco Podimane: 30/7/1925 - 14/9/2015’, photograph by unknown.